"It's falling like in Gravelotte"

Dec 26, 2013 15:15:20 GMT

Post by Deleted on Dec 26, 2013 15:15:20 GMT

"Ca tombe comme à Gravelotte" is an expression recognized throughout France, but people in most of the country know nothing about its origin. It is one of the equivalents of "it's raining cats and dogs," so, once people have absorbed the information that a downpour is in progress, they don't really worry about analyzing the etymology.

I have known just about all there is to know about what happened in Gravelotte since early childhood, because this village is only 9 kilometres from the village of my grandparents. In fact, the biggest surprise to me was finding out that it wasn't just a local expression in the region but was known nationwide. Gravelotte is not even as big as my grandparents' village, but it is along the N3, which was the major national highway from Paris to Forbach and Saarbrücken before the A4 autoroute was built. And before the highways were even numbered, it was quite officially called "the road to Germany."

I have known just about all there is to know about what happened in Gravelotte since early childhood, because this village is only 9 kilometres from the village of my grandparents. In fact, the biggest surprise to me was finding out that it wasn't just a local expression in the region but was known nationwide. Gravelotte is not even as big as my grandparents' village, but it is along the N3, which was the major national highway from Paris to Forbach and Saarbrücken before the A4 autoroute was built. And before the highways were even numbered, it was quite officially called "the road to Germany."

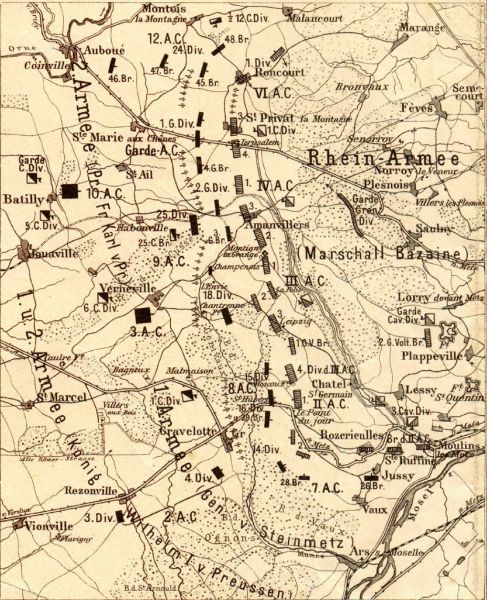

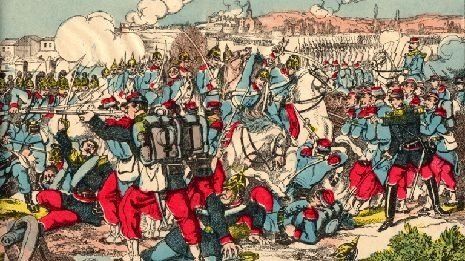

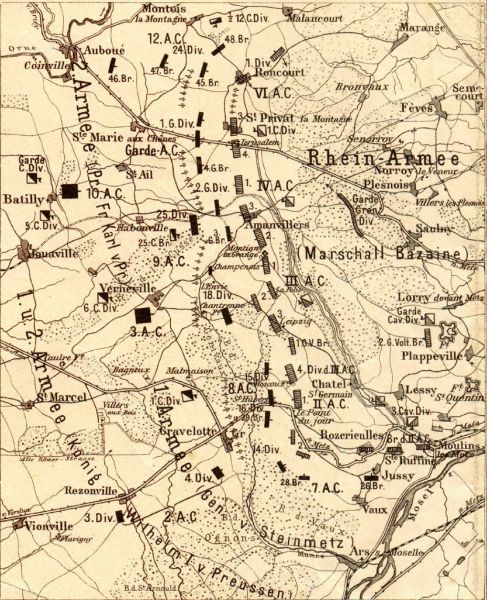

What made Gravelotte famous, however, was a famous battle in the war of 1870 -- the "battle of Gravelotte" -- that is the official German name. The official French name is the "battle of Saint Privat" but I have never heard people call it by any name other than "Gravelotte" which is where most of the people died.

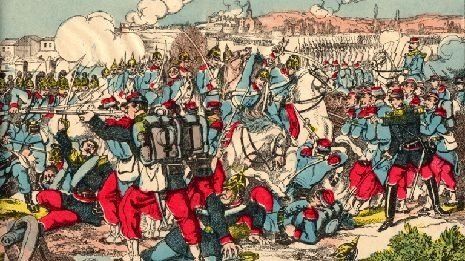

Basically, the whole reason for the battle was to free Metz, which was almost completely surrounded by the Prussian army. However, the French generals completely bungled their strategy by not putting enough troops into the field. The French light artillery mowed down Prussians, but the Krupp cannons on the other side were equally lethal against the French troops. In the end, it turned into hand-to-hand combat in the fields around Gravelotte, and the bayonets had a, uh, field day.

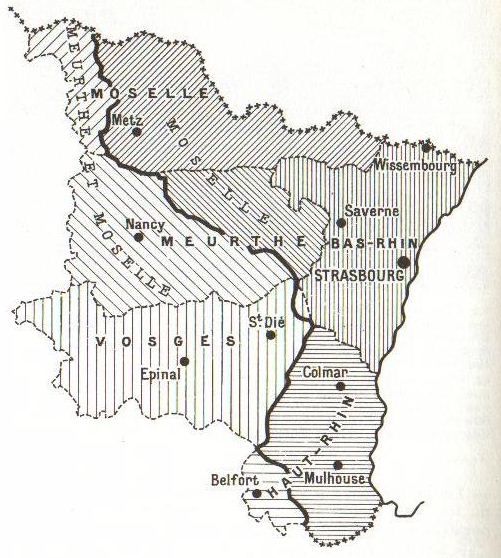

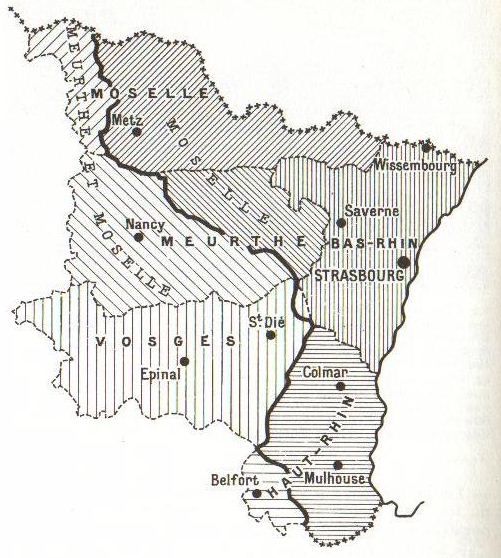

The Prussians won the battle, and the siege of Metz could begin. This battle was considered to be the determining factor of the war and sealed the ultimate defeat of France. After the birth of the German Empire, which was proclaimed humiliatingly in the hall of mirrors of the Château of Versailles, the treaty of Frankfurt was signed, ceding part of France to Germany.

Gravelotte was originally supposed to remain in France, but the Prussian army had suffered such heavy losses that Kaiser Wilhelm felt it was essential that it become part of Germany, as the battlefields were considered to be sacred ground. So a few modifications were made and it was the city of Belfort in southern Alsace that lucked out, because a tiny French department (which still exists) was created and named "Territoire de Belfort" in exchange for the land around Gravelotte.

My grandfather's family lucked out as well, because their village of Batilly became a border town -- in France. In fact, the village even developed because of this because it was on a rail line to Metz, and it became the customs station for goods and a whole bunch of rails were built to keep the waiting freight cars.

Okay, back to Gravelotte. I went with my grandfather to Metz dozens of times on the road that went through Gravelotte. As mayor of the village, he would have "business" at the Banque de France in Metz regularly -- I suppose that he deposited the money for fiscal stamps which were stuck to just about everything back then -- hunting licenses, identity cards, passports, notarized documents, etc.

I would see things along the road, out in the fields -- isolated crosses just standing in the wheat fields and meadows. They were nothing like the neat military cemeteries for "14-18" or "39-45" as the wars of the 20th century are called in France. I knew they were graves for the war of 1870 (since my grandfather told me so), but it just seemed so strange that they would be out there by themselves where nobody would ever visit them. I was determined to see them for myself one day.

These are not the crosses that I saw as a child, and there are not nearly as many of them as there used to be. I did a bit of research and learned that most of them were "consolidated" in 1980. I imagine that there were some negotiations between the French and German war commissions, but that the complaints of French farmers won out in the end -- their fields were peppered with these things and they were a major obstacle to French agricultural machines.

What made Gravelotte famous, however, was a famous battle in the war of 1870 -- the "battle of Gravelotte" -- that is the official German name. The official French name is the "battle of Saint Privat" but I have never heard people call it by any name other than "Gravelotte" which is where most of the people died.

Basically, the whole reason for the battle was to free Metz, which was almost completely surrounded by the Prussian army. However, the French generals completely bungled their strategy by not putting enough troops into the field. The French light artillery mowed down Prussians, but the Krupp cannons on the other side were equally lethal against the French troops. In the end, it turned into hand-to-hand combat in the fields around Gravelotte, and the bayonets had a, uh, field day.

The Prussians won the battle, and the siege of Metz could begin. This battle was considered to be the determining factor of the war and sealed the ultimate defeat of France. After the birth of the German Empire, which was proclaimed humiliatingly in the hall of mirrors of the Château of Versailles, the treaty of Frankfurt was signed, ceding part of France to Germany.

Gravelotte was originally supposed to remain in France, but the Prussian army had suffered such heavy losses that Kaiser Wilhelm felt it was essential that it become part of Germany, as the battlefields were considered to be sacred ground. So a few modifications were made and it was the city of Belfort in southern Alsace that lucked out, because a tiny French department (which still exists) was created and named "Territoire de Belfort" in exchange for the land around Gravelotte.

My grandfather's family lucked out as well, because their village of Batilly became a border town -- in France. In fact, the village even developed because of this because it was on a rail line to Metz, and it became the customs station for goods and a whole bunch of rails were built to keep the waiting freight cars.

Okay, back to Gravelotte. I went with my grandfather to Metz dozens of times on the road that went through Gravelotte. As mayor of the village, he would have "business" at the Banque de France in Metz regularly -- I suppose that he deposited the money for fiscal stamps which were stuck to just about everything back then -- hunting licenses, identity cards, passports, notarized documents, etc.

I would see things along the road, out in the fields -- isolated crosses just standing in the wheat fields and meadows. They were nothing like the neat military cemeteries for "14-18" or "39-45" as the wars of the 20th century are called in France. I knew they were graves for the war of 1870 (since my grandfather told me so), but it just seemed so strange that they would be out there by themselves where nobody would ever visit them. I was determined to see them for myself one day.

Well, it took more than 50 years, but I finally did so last week. I parked the car at the only monument next to the road.

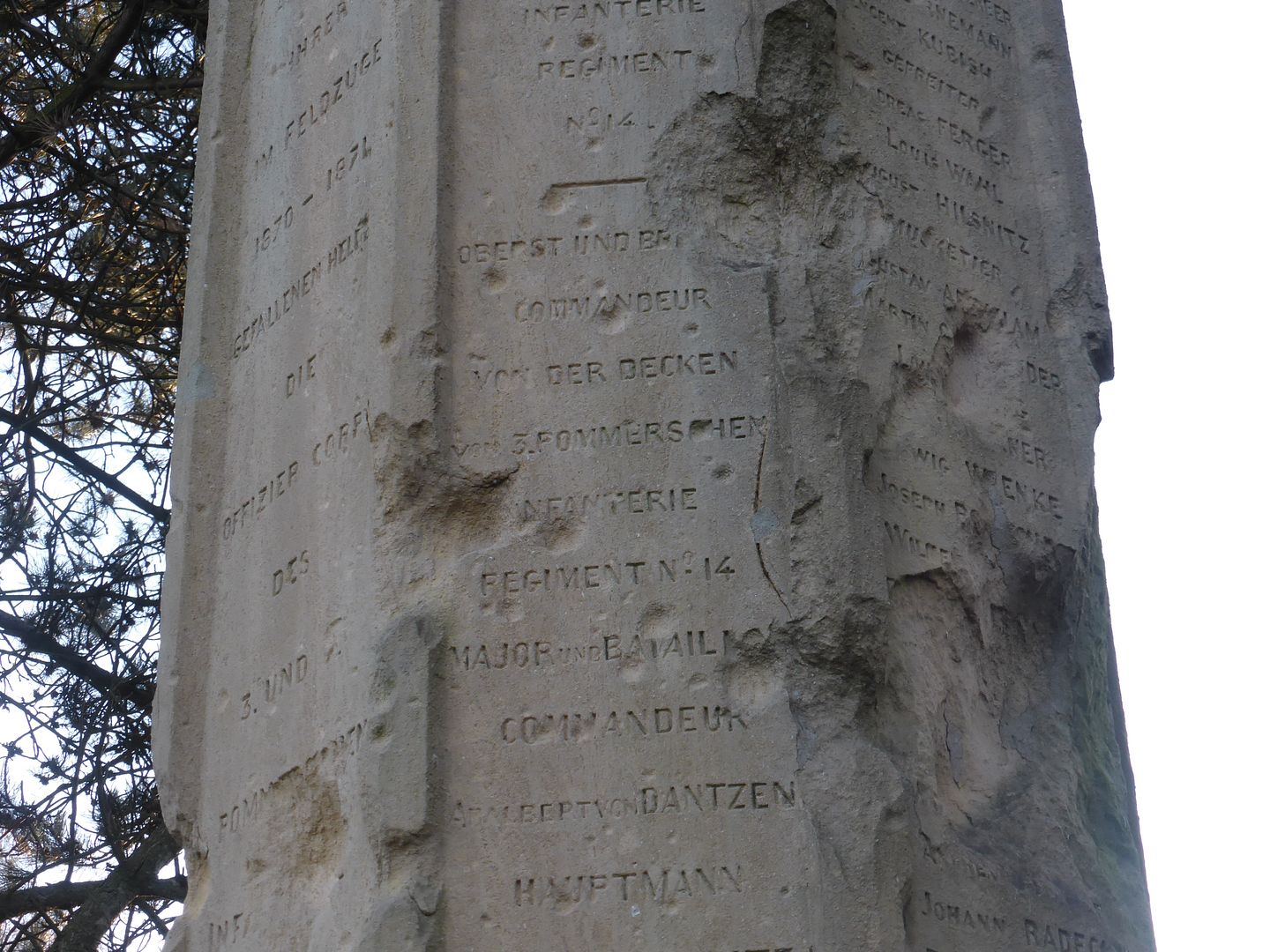

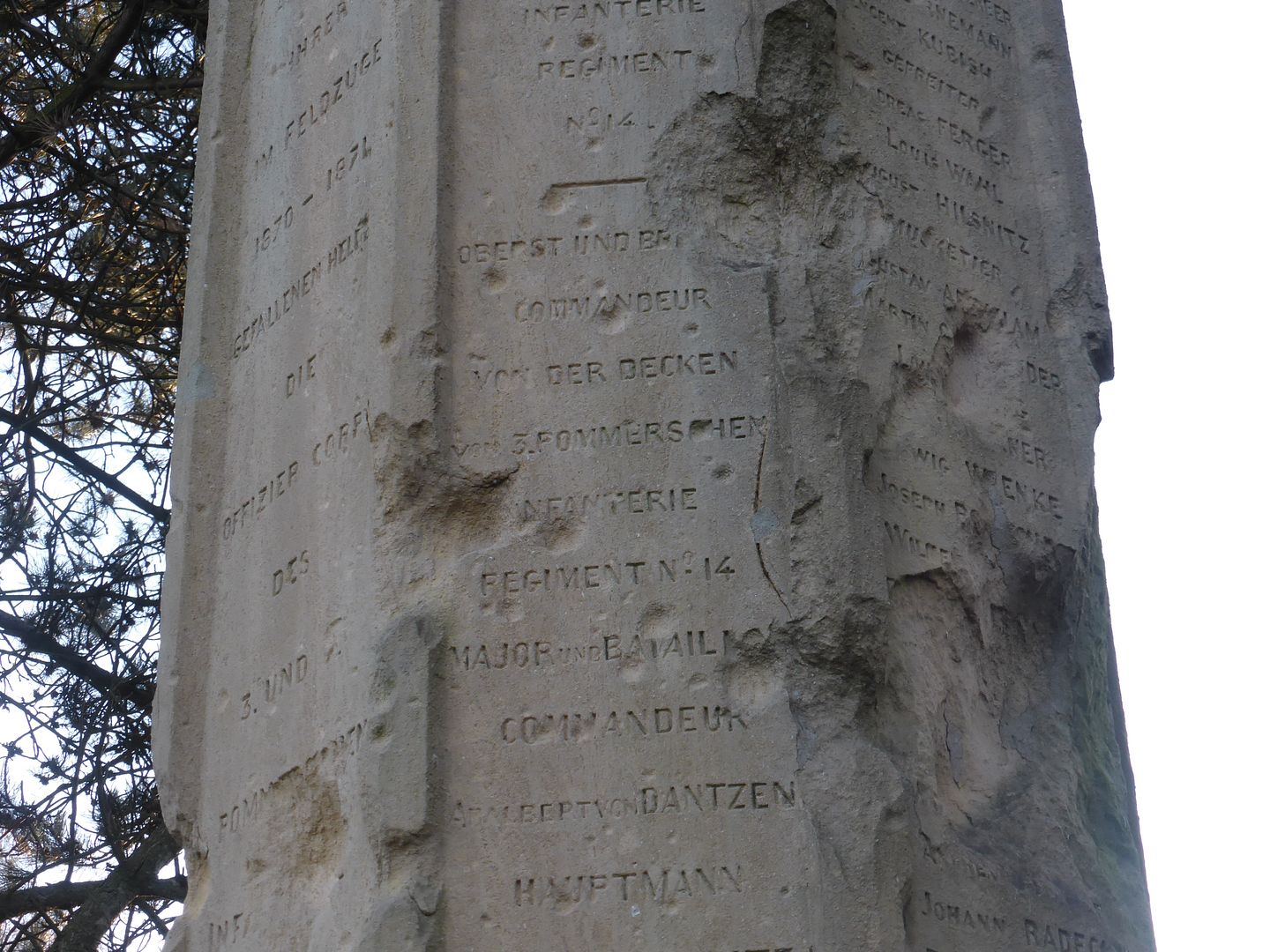

It is still sacred ground to the Germans, even though it is in France now. They are the ones who placed the monuments here.

Other wars have taken their toll on the stones in the meantime.

They are actually collective graves rather than individual ones.

It is still sacred ground to the Germans, even though it is in France now. They are the ones who placed the monuments here.

Other wars have taken their toll on the stones in the meantime.

They are actually collective graves rather than individual ones.

These are not the crosses that I saw as a child, and there are not nearly as many of them as there used to be. I did a bit of research and learned that most of them were "consolidated" in 1980. I imagine that there were some negotiations between the French and German war commissions, but that the complaints of French farmers won out in the end -- their fields were peppered with these things and they were a major obstacle to French agricultural machines.

But there are still a few left out there.

Peace has returned to the fields of Gravelotte, forever, I hope.

Peace has returned to the fields of Gravelotte, forever, I hope.